"This will be quick to design, right?": Thoughts and guidelines on UX Sizing

Does it feel challenging to build enough design time into your team’s sprints? Have you struggled to feel understood, when making the case for design lead-time before handing things off to engineering? As designers, we’ve all been there. Especially for organizations in the early stages of establishing a design practice, or when colleagues are new to incorporating UX into planning, it can be challenging to explain the breadth and detail that goes into delivering solid designs.

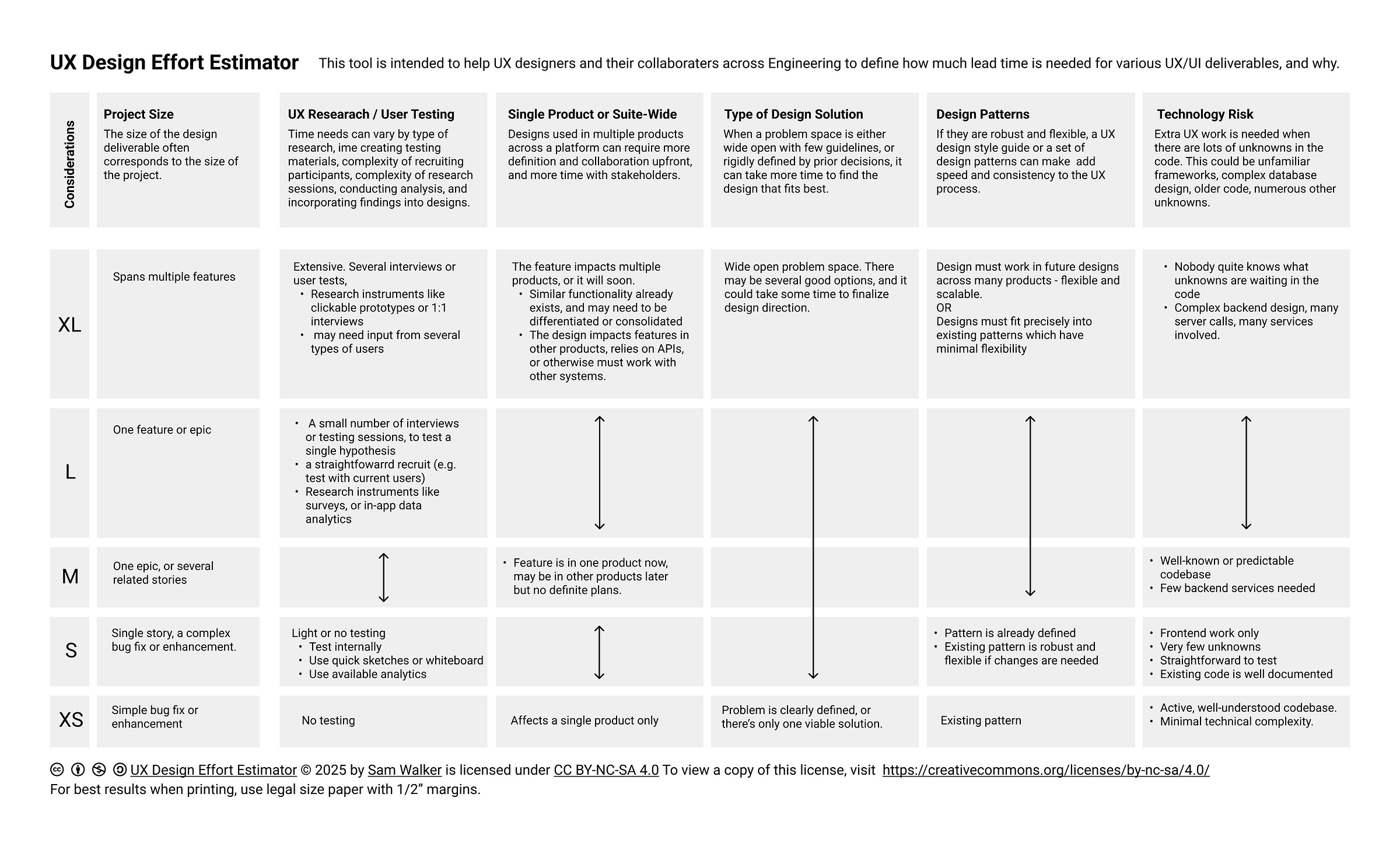

My aim here is to set out some thoughts on estimating design effort, and to provide a visual tool that can be used in a couple of ways:

A repeatable, granular approach that UX practitioners can use to size their own tasks.

A collaborative tool for Engineering colleagues to reference, to help align on UX processes and planning needs.

I created this sizing tool while working at an organization that was early in its UX journey. Many of the teams hadn’t incorporated design into their Agile practice before. Including design needs in sprint planning was challenging sometimes; even when we were all aligned on the benefits of UX, we lacked a shared language for the tasks and variables involved in design delivery.

My goal for this tool was to use it with teams as an explainer and rationale for UX sizing. Additionally, I wanted to make it available to new PM and Engineering leads as part of their onboarding, to help us get synched from the outset. I kept the visual to 1 page so that my colleagues could glance through it quickly as needed, rather than dedicate extensive time to it like documentation or a training.

After refining the tool with our lead PM and VP of Engineering, I socialized it with my teams. It helped significantly - especially in sprint planning, and in establishing shared expectations when new PMs and Engineers joined the teams.

Please feel free to use this sizing tool in your own UX practice. Some additional context to keep in mind while using it:

Sizing – The tool uses t-shirt sizing as an example. Fibonacci or other sizing norms can be used instead. Exact sizing for a project will also depend on organizational factors like how many designers are staffed to projects, the level of design fidelity required, and the level of UX involvement in writing tickets and reviewing features prior to release.

Project Size – This one’s relatively straightforward. It usually takes longer to design an epic than a single story. Size estimations for Engineering and for Design tend to work similarly here, so this can be a great starting point for building shared understanding.

User Research & User Testing – When there is a significant research component, design delivery time also must account for research planning, participant recruitment, moderating sessions, and data analysis. It is vital to build lead-time for these activities into planning. Projects where significant research is an ongoing part of the design scope are good candidates for moving design pre-work, such as research, outside of the Engineering sprint cadence.

Research and testing are grouped together in the tool, but for some projects it might be helpful to consider them as separate variables. If research sizing consistently comes in high, that could be a sign to consider adding dedicated UX Research staff to the project.Scale & Reach – A design which will only ever be used on one page of one product can be implemented in whatever way is simplest. But very little of our modern digital environment is simple – and for good reason. Designs that must integrate with or be re-used by many different products and systems come with a lot of complexity. Making the time upfront to identify the design requirements around scalability and re-use, and deliver against those needs, usually saves time in the long run. Those designs can be re-used as patterns or design system components.

Known-ness of Solution – The design effort has a good chance of being small if: 1) the needed solution is already in use elsewhere in the system, 2) it’s a styling update on otherwise-stable legacy functionality, or 3) the solution is fully defined in an established design system. The design may also be small if the inverse is true – if the solution is a one-off that will never be re-used (e.g. if it sizes XS in the Scale & Reach category). But if the solution is entirely greenfield work, the unknowns are likely to be many. There will likely be pre-work collaborating with Subject Matter Experts to define the problem space, or working with a Business Analyst to get clear on requirements. If a project is sizing high in Known-ness, double-check its sizing for User Research & User Testing – that one often ends up high as well.

Design System / Patterns – New designs will save time and reduce design effort when they can be made mainly out of existing design system components and patterns. Creating new components from scratch sets a lot of new precedent, which can have significant knock-on effects. Designing new components will increase the initial effort, with that effort recouped over time as the component gets re-used across systems.

An established design system can be a sign of organizational maturity. But so can consistent use of a specific React or Angular library. Prioritizing re-usable components is a great spot for collaboration with Engineering; solutions may vary, but priorities nearly always align.Technology Risk – This is out of any designer’s control. But it can have a big impact on design delivery, success, and timing. Because designers are nearly always working within or designing to alleviate technical constraints, it is beneficial to understand technical risks as early as possible. For example, a particular database may need lazy load for tables in order for its data to be performant, or a product acquired from another company may not use the components that are standard internally.

This tool is designed to be flexible. It has served me well across a range of design environments, but it does not work exactly the same across them. This can look like:

B2B – Designing for complex, one-off software tools sometimes means technology risk that is greater due to tech debt or legacy solutions. On the other hand, it’s sometimes possible to reduce research time by establishing a standing Customer Advisory Board which can streamline information gathering and design feedback.

B2C – A diverse userbase and strong motivations to provide intuitive UIs can mean robust design systems and readily available user analytics. Access to analytics data can offer options for quick turnaround on research questions. In some cases, more predictability around Design Systems/Patterns can speed work – in other cases, designing a new component or establishing a multi-product pattern may require additional time for cross-team input and collaboration.

Consulting – The time spent navigating unknowns may be high compared to product companies, if technical staff don’t have full visibility into the systems they’re supporting. However, some resources may be very clear in ways that speed design – such as access to stakeholders, and a contractually-specified project scope that is unlikely to unexpectedly shift.

Public Sector – Additional emphasis on planning and user testing should be expected, to assure that public dollars are spent thoughtfully. Design patterns may need to consider several bureaus’ worth of user experiences, since it’s important to keep design as consistent as possible across the various services a member of the public might engage with.

Startups – Utilizing one-off design solutions in the name of iterating quickly might reduce UX time in the short term. But startups with plans to scale still need to build a base of repeatable, systematized designs. These take time to plan and implement. Consider earmarking some design time for tasks like establishing a design system and defining user roles in a way that Engineering, Product, and Marketing can all align on. This can form a basis for future user research efforts or requirements writing. While these tasks initially sit outside of sprint work, they can reduce the UX effort needed for stories or epics in the long run.

The answer to “how long will that take to design?” is always “it depends.”. However, this tool can help designers plan their approach and their expected effort on projects. It can also support communication with colleagues and stakeholders about the many facets that shape the design process.

Note: I initially drafted this article while working at Pluribus Digital. I would like to thank Kristina Parrill and the Pluribus staff for their feedback and support.